It is a quiet Sunday afternoon in Karachi as I head out to meet Ali Zafar – who is presently staying at Ahsan Rahim’s residence and is scheduled to head back home to Lahore in a day or two.

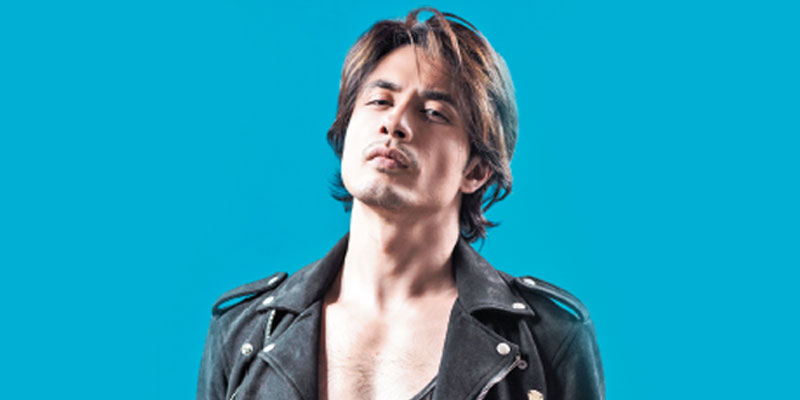

Standing at the door to receive me in a white kurta pajama, he looks nothing like the glamourous superstar we saw in Coke Studio 10 while he was singing ‘Julie’. The swagger with which he carried the song is nowhere to be seen and is replaced by a calm, composed Zen-like demeanor. I know I’m being greeted by a man who is genuinely content with life and everything it has to offer.

Part of the reason is that Zafar has seen the pinnacle of success, both at home and abroad, with the understanding that fame is simply a by-product of good work and is as fleeting as it is fickle. He is more content and happy today than at any other previous moment in time and it shows in the way he addresses my questions.

Another equally important reason is the amount of work he has done since appearing on the horizon more than a decade ago. Films, concerts, studio albums, tours, commercial projects, jingles, music videos, collaborations, soundtracks, covers – he has done it all and on most occasions he’s done it well.

Above all, Zafar is clear about who he is catering to and it is not a niche audience but the man on the road who is already living through a nightmarish reality and needs some respite that can be provided by an entertainer like him.

The one thing he has never done is feature in a Pakistani film and that is being addressed with Teefa in Trouble – which is where this conversation begins.

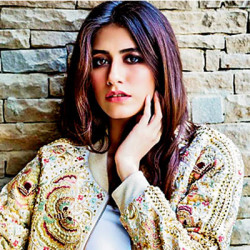

I ask Zafar to elaborate on the process he went through while filming Teefa in Trouble, which is shot partly in Lahore and partly in Poland and features the superstar opposite Maya Ali. What are the learnings from India that he thinks can be applied to Pakistan?

“I had been wanting to make a Pakistani film for the last four-five years,” he begins. “When I ventured out into Bollywood and saw the infrastructure, I realized that as an industry it is so huge and powerful that an image of India is being projected through it to the world. It has also given livelihood to so many people. So film is an industry in itself and it should be viewed as such.”

Zafar notes that with the creative collapse of the film industry in Pakistan that persisted for decades, artists like him needed to go to India to get work as actors; the film industry revival in Pakistan hadn’t happened back then.

“When I went to India in 2008 to shoot Tere Bin Laden, there was no Pakistani cinema and no films were being made and I always wondered when we would make our own industry. While shooting David Dhawan’s Chashme Badoor there was an idea that came to me. And subsequently there were many ideas that me and Ahsan (Rahim) bounced off each other until we reached Teefa in Trouble. From the moment the idea was born (last year) to the pack up of shooting, it was all done miraculously in the time span of under one year, which is very rare. This was a film that was meant to happen and had its own destiny. It came at the perfect time.”

Having worked in seven contemporary Hindi films with a number of directors, actors and technicians, Zafar agrees that applying learnings from that experience was both necessary and helpful.

“I had read 150 odd screenplays and scripts. Some films I starred in worked while some didn’t and you learn much more from failure. Those learnings were applied to Teefa in Trouble. Add to it Ahsan’s enormous experience and the lifetime of work he has done with artists like Shehzad Roy, myself, Abrar ul Haq and others and I can say we’ve put in our best. It was a way for us to also contribute to the Pakistani film industry and be part of the wave that is rebuilding the industry.”

When asked what he makes of the Pakistani audience and their expectations, Zafar says that the audience has shown a great deal of patience and restraint when it comes to local content in cinemas. “Anything that is above average, they (audience) have bestowed a lot of love on it.”

However, he is also clear that if you give the audience material that is less than average, they won’t embrace it.

“They feel cheated if you give them a bad film. It is essential that as filmmakers we keep in mind that we must make good films. In order to do that though, there is a certain process that you need to go through, which is the process of learning. For example, what is a screenplay. All the knowledge and information is there. When we started Teefa in Trouble, I studied books on screenplays to learn how it’s done. We need to think out of the box and see how international cinema works and not just Bollywood.”

He adds: “People by and large have become more aware of things and truth and they have easy access to knowledge and information and they are sharing it with each other so you cannot fool them. People will reject things that do not appeal to them aesthetically or intellectually. They want meaningful content and it doesn’t mean a lecture. What it means is that people want to be entertained with substance. Even in India, films featuring big actors have not done well in recent times because you can no longer rely on star-power alone to succeed. It’s a good thing.”

As for the subject matter of Teefa in Trouble, Zafar describes it as a romantic/action/comedy and maintains that the film is not senseless.

“The objective is not to appeal to three critics. It is to please all those people who will come to the cinema. But at the same time it should also appeal to your own aesthetics.”

As the conversation goes on, Zafar is quoting Abraham Lincoln and Rumi verbatim while trying to elaborate a point and it’s palpable that he has a philosophical, thoughtful side that is rarely seen and is often eclipsed by the playful demeanour that he wears onstage.

Zafar is also embracing values of altruism by having founded the Ali Zafar Foundation that exists with the aim of working on issues that affect primarily women and children such as education, health and basic rights.

“In this country we have suppressed women. The idea is to raise these issues in one’s work in a manner that is subtle. I no longer wish to do things that are purely entertainment. There has to be some meaning to it. Even in a song like ‘Julie’, there is a message. It has to do with evolution and if you’re not thinking about your environment and the people around you and always thinking about your own success, then it’s a very selfish life. I think, in a lot of ways, some of us are living a selfish life because we are only thinking about ourselves. The shift that needs to happen in human consciousness is that we need to start thinking collectively. We should collaborate and work together to benefit others. And artists such as myself have a greater responsibility. Our responses should be responsible.”

The one value Zafar has wholeheartedly incorporated in his personal and professional life is an absolute belief in power of positivity.

“One should always think positively. Even when you’re criticizing something, the end result should be positive.”

As Zafar puts it, this embracing of positivity has come from training. “You have to train your mind and not let the negativity affect you. When you start seeing human beings as a species who will behave in a certain manner then you start to understand their reasons and learn that you shouldn’t take it to heart. It is achieved through prayer, meditation and self-belief. It is about reciprocating negativity with positivity and love.”

When asked how he copes with the presence and meteoric rise of several others in recent years and whether there is fear that the stardom will fade or be eclipsed by others, Zafar abstains from pulling down anyone else.

“Okay, so there are two things. One, worry and fear are useless emotions,” he says while sipping on green tea. “Fear was put into man so he could survive in nature. I don’t fear and worry about anything particularly since the realization that everything that was created and born and came into this planet has to go away. If I felt or feel that I’m invincible and nobody can be better than me or go higher then that would be the most stupid thing I or any star could do to himself. It will lead to his own self-destruction.

Second, when you start thinking collectively you will learn that it’s all a process and will unfold in its own way, in its own time. More people will come in and they should and down the line you should be able to see that ‘okay I contributed and now it’s time for me to move on and maybe do something else’. You can’t always expect people to see you in the way they did when you first started out. I feel happy when I see new people come in.”

The musician, the family man Zafar has enough personality to be a permanent modern-day movie star but thankfully the musician in him is alive and kicking as well. But a lot has changed since he made his musical debut with ‘Channo’ and he knows it too. One major change has been the birth of Coke Studio that is in its tenth incarnation and has both followers and detractors. But Zafar is clear about what the show has achieved.

“The way music was seen and consumed has changed. After the conclusion of Indus Music and presence of several other issues like umpteen news channels, a lull came where no one knew what to do to improve things. Then came Coke Studio that gave people a chance to do music. I know during Rohail Hyatt’s tenure as well as under Strings’s tenure, they received entries from all over the country and they chose the best of the best to come and perform at this platform. Singing live amidst all these musicians in a single take requires confidence, skill and talent. And I’m sure they have a lot of boxes to tick off. But you must notice that Coke Studio didn’t just feature stars alone. Coke Studio made stars and a lot of new people have been seen on the show. Some of them will leave a mark while others will be unable to do so.

Second, it has to be a fine balance between established and non-established artists. In the initial years, established artists redid their own material and were fusing it with others. Then slowly, newcomers were given a chance. And the show has produced a lot of stars now including Ali Sethi, Aima Baig and Momina Mustehsan. However, Coke Studio also has a limit and they can only take so many people in one season.”

As the conversation comes to a close and I ask Ali about raising a family in Pakistan where political upheaval and violence is every day routine, his philosophical side emerges one more time.

“Some concepts have always been clear to me. One of those concepts was that of family,” says Zafar on a parting note. “I knew that one day I would get married and have children and prioritize family over everything. Life is about balance. I have a very supporting family and wife and loving children. If I need to go on soul-searching or work, they understand and they’re with me and I’m with them. As far as security is concerned you can only do so much. As a father and as a family man it’s my responsibility to give them everything and I do. At the same time, you have faith in God. Fear has a way of manifesting itself and I don’t allow myself to fear anything.”